urban astrophotography

current setup, nj, 2025

space

In 2014 I saw the milky way for the first time. Space had always intrigued me, but in a late night “dude aliens would be crazy” kind of way vs anything approaching academic. Seeing that cosmic might in full color gave me a newfound deep appreciation and admiration for the sky above.

I got my first telescope in the summer of 2020. I was riding out the pandemic in Maine, relatively free from light pollution, and went down a youtube rabbit-hole on much of the tech powering modern deep space imaging, and decided I wanted to participate. Initially I left off the camera and did purely visual astronomy. This was fun to see the rings and moons of Saturn, but left me wanting more.

imaging

In 2024, I decided to invest in my first “smart” setup consisting of a an entry-level motorized mount, a thinkpad, and a fujifilm digital camera slapped on the end of my planetary scope.

first setup, 2020

The first few nights consisted of frustrating debugging sessions til I’d inevitably call it at ~1am to get a reasonable amount of sleep. In the coming weeks I’d order missing parts, get a dedicated, cooled astrophotography camera, mess around in a sea of processing software, and, finally, produce an image.

core of andromeda, 2024

leveling up

I caught the bug. I live in Jersey City primarily, and didn’t want to wait for the precious few weeks I could spend with my parents in Maine, so I decided to rebuild my kit from scratch with a focus on mobility. I would be imaging from my roof, or heading to local dark sky sites, so being able to set up and tear down quickly was a key motivator.

mobile setup, 2025

It uses an integrated primary camera, guide camera, and computer, allowing it to fit compactly and travel well, with teardown and setup taking <10m. The integrated computer moves the control flow to my smartphone via ASIAir. The interface is much simpler than that of the thinkpad, and allows me to further monitor from a distance.

ASIAIR App

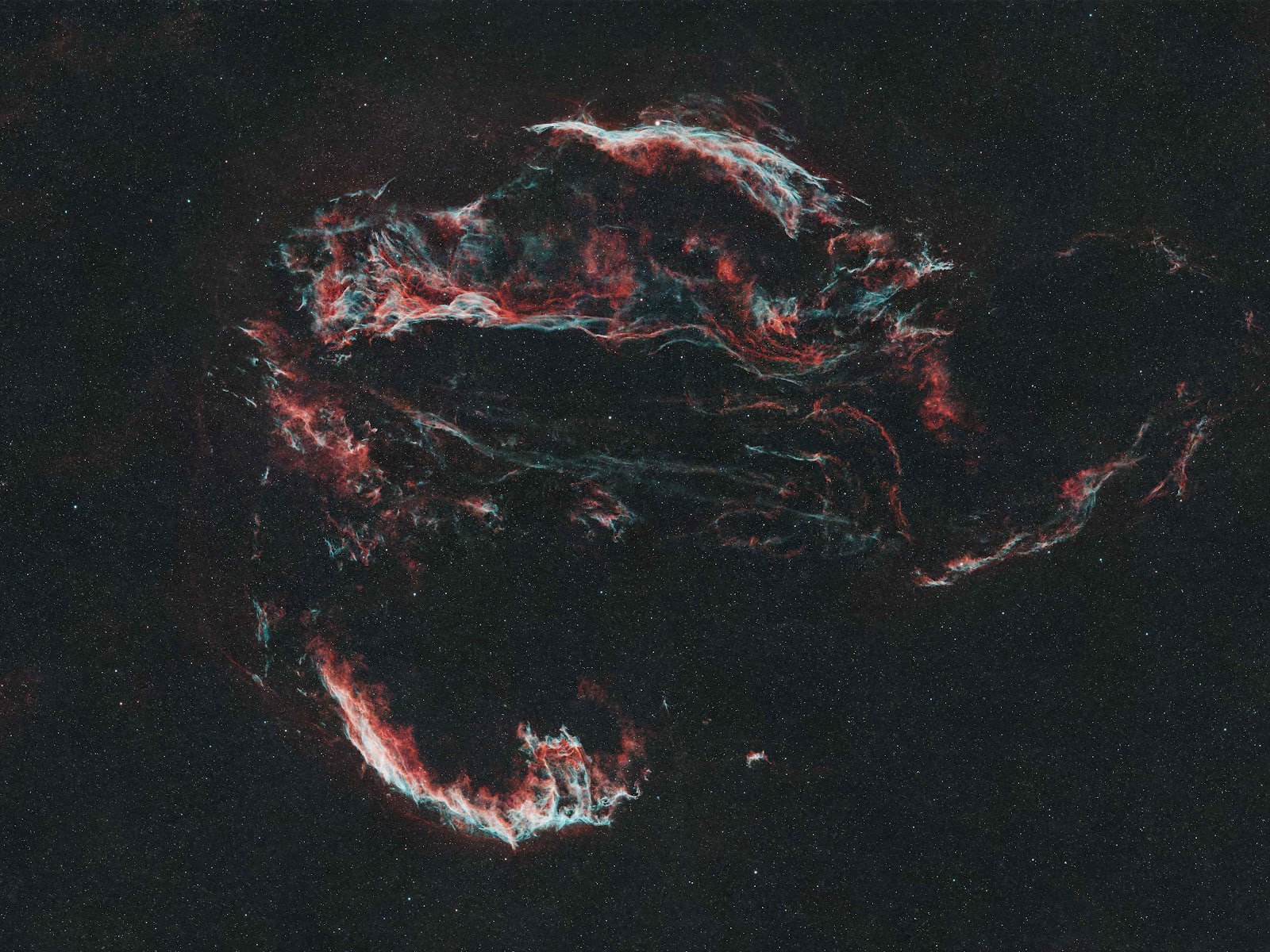

There’s a lot of light pollution in most cities, with Jersey City sitting at a bortle 8. To allow for high quality deep space imaging, light filters are necessary. I use a specialized H-Alpha OIII filter to limit the received light to a 7nm wavelength which constrains the signal to mostly light emitted from emission nebulae. While this is a limit on the types of targets I can shoot, it allows high quality imaging of those targets, with minimal light pollution impact.

Once I have my individual images, I stack them using software like PixInsight to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Some slight edits follow, allowing for some creative liberties (boosting color, contrast, dimming background stars, etc). Editing can make or break an image, and I’m still far from great at it.

Finally, after integrating 9 hours of exposures, results!

veil nebula, 2025

astrobin <- more images here

I’m still quite new to the hobby, but am excited to keep honing my tools and abilities. Deep space astrophotography is a way to look back in time, an experience otherwise inaccessible to us here on Earth.